DB Pension Transfers: Getting Advice Right

Understanding the benefits, pitfalls, and practical considerations of advising on pension transfers...

I've noticed an increase in firms seeking paraplanning support with defined benefit (DB) transfers in recent months. That uptick reflects a rise in client enquiries, likely driven by three main factors:

- CETVs have modestly increased. After three consecutive monthly falls, June 2025 saw the first month-end increase of the year, with the XPS Transfer Value Index rising to £141,000. This is still about 10% below mid-2024, and nowhere near the peaks of 2016–21, but it’s enough to spark client curiosity.

- Schemes are strongly funded. According to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) 7800 Index, DB schemes collectively held a surplus of around £241bn in August 2025, with an average funding ratio of 127.7%. Well-funded schemes often increase communications, which in turn prompts member enquiries.

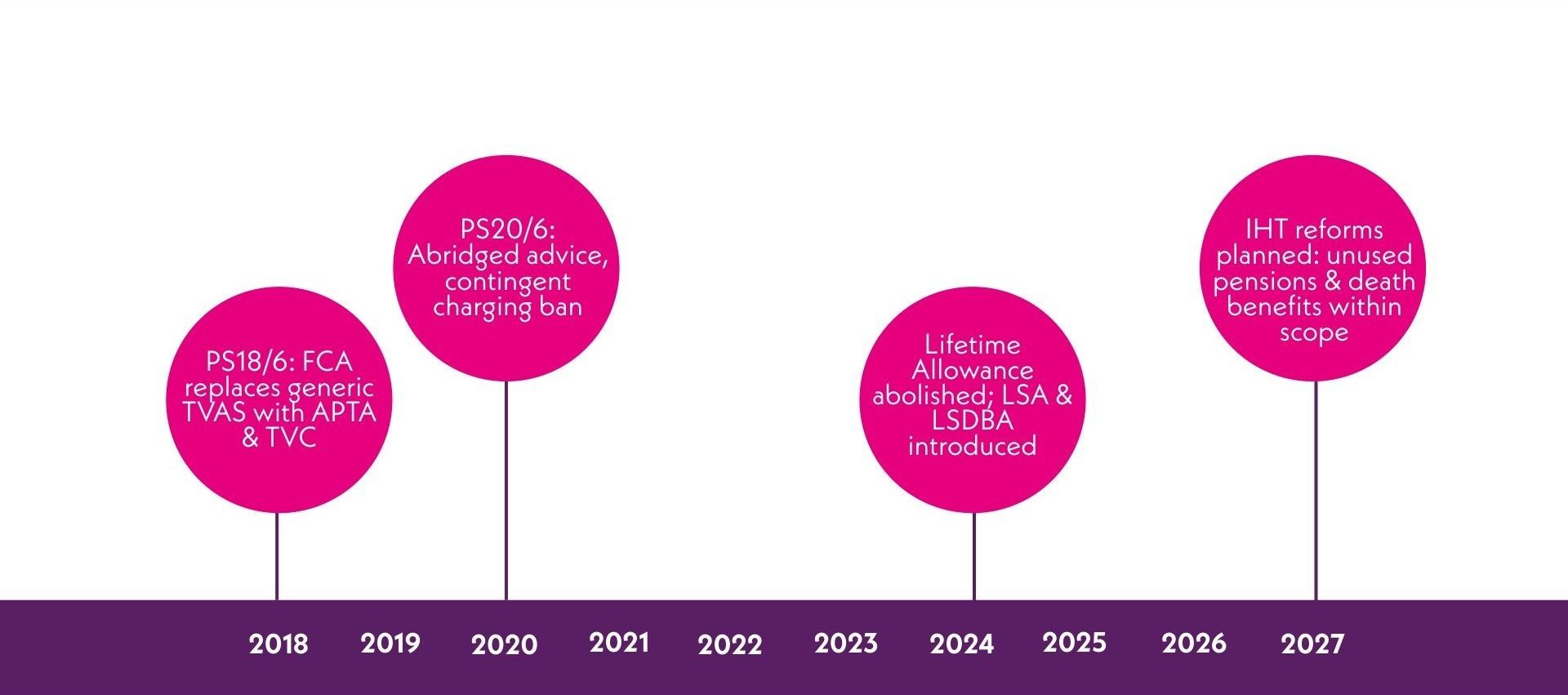

- The changing tax regime. The Lifetime Allowance (LTA) was abolished from April 2024 and the Lump Sum Allowance (LSA) of £268,275 and the Lump Sum and Death Benefit Allowance (LSDBA) of £1,073,100 were subsequently introduced. For clients with estate-planning issues this reframing is significant; however, the picture is complicated by the government’s confirmed plans—subject to the passage of final legislation—to bring most unused pension funds and certain lump-sum death benefits within the scope of IHT from 6 April 2027. Draft legislation has been published following consultation, and further HMRC guidance is expected; I’ll discuss the implications later.

The result? Clients are once again asking their advisers whether a pension transfer is right for them. But interest does not equal suitability. The FCA’s starting point that DB transfers are unsuitable remains firmly in place. For advisers, the challenge is to handle enquiries rigorously, ensure files can withstand scrutiny, and, where a transfer is genuinely in the client’s best interests, build a clear, evidence-based case.

Understanding DB schemes and transfers in Practice

To understand the issues surrounding DB transfers, we must first appreciate what a Defined Benefit pension scheme actually is and why it is such a valuable asset. These schemes, now largely closed to new entrants, were once the backbone of occupational pensions in the UK. They promise members a level of retirement security that few other arrangements can match. At their core, they transfer investment, inflation, and longevity risk away from the individual and onto the scheme sponsor. The value of that promise is often underestimated until it is placed side by side with the alternatives.

The mechanics of DB schemes

A Defined Benefit scheme promises a pension income for life, typically calculated using an accrual rate multiplied by years of service, and based on either the member’s final salary or career average earnings. That income is typically indexed to inflation, providing protection against the erosion of purchasing power over time. Most schemes also build in survivor benefits, ensuring that a spouse or dependent continues to receive income after the member’s death.

There are variations in design:

- Final Salary schemes calculate benefits based on the member’s pay towards the end of their career, often the most generous outcome.

- Career Average Revalued Earnings (CARE) schemes calculate benefits on each year of service and revalue them annually, usually with reference to inflation. These are often less generous than Final Salary but still provide a valuable guarantee.

- Some schemes are hybrid, combining DB-style guarantees with elements of defined contribution accrual.

- The public sector landscape is different again. Many large unfunded schemes, such as the NHS or Teachers’ Pension Schemes, do not allow transfers out into defined contribution arrangements (other than through the Club transfer system between public service schemes). For most private sector members, however, the option of a transfer exists, and with it, the need for advice.

The distinctive feature of a DB scheme is that the risks lie elsewhere. Inflation risk, investment risk, and the risk of living longer than expected are all absorbed by the sponsoring employer and, ultimately, underpinned by the Pension Protection Fund (PPF). For the member, the promise is

simple: a known income for life, regardless of market conditions.

Replicating that promise in the open market is expensive. An inflation-linked, guaranteed annuity for life requires significant capital. This is why DB schemes are regarded as “gold-plated”, and why the FCA insists that the default assumption must be that transferring away is unsuitable.

The cash equivalent transfer value (CETV)

The CETV is the mechanism by which members can swap DB benefits for a pot of capital in a DC scheme. It is an actuarial calculation of the present value of the member’s promised future benefits. The CETV is influenced by several factors:

- Discount rates, usually linked to long-dated gilt yields. The higher the yield, the lower the CETV.

- Inflation assumptions, which drive the cost of providing indexation.

- Longevity assumptions, which estimate how long members will live.

- Scheme funding and trustee discretion, which can influence transfer terms.

This explains why CETVs have fluctuated so dramatically over the past decade. Between 2016 and 2019, when gilt yields were at historic lows, CETVs soared to unprecedented levels, often 30 or 40 times the annual pension. When rates rose sharply in 2022 and 2023, CETVs fell, sometimes by 40% or more. Today, in 2025, they remain subdued compared with the peaks, though modest increases in recent months have reignited client curiosity.

The tension between guarantees and flexibility

The central dilemma of DB transfers is the tension between the value of guarantees and the appeal of flexibility. A DB pension locks in income security for life, but it does so at the cost of flexibility. The member cannot choose to draw more in early retirement and less later. They cannot usually take ad hoc lump sums beyond the tax-free PCLS. And survivor benefits, while valuable, are rigid in form and subject to tax.

By transferring to a DC scheme, members gain flexibility. They can structure withdrawals to suit their evolving needs, access lump sums, plan around tax allowances, and manage death benefits more creatively. But they also inherit investment risk, inflation risk, and longevity risk. For some, that trade-off makes sense. For most, it does not.

The regulatory framework

The regulatory landscape around DB pension transfers has evolved dramatically over the past decade, and it is impossible to advise competently in this space without understanding the path that has brought us to the present. Each rule, policy statement and piece of guidance has been a reaction to real-world outcomes: surges in transfer activity, unsuitable advice, client losses, and systemic risks. What we have today is the culmination of years of tightening, clarification, and overlay of new principles, most recently Consumer Duty.

PS18/6

The FCA’s Policy Statement 18/6, published in March 2018, was the defining shift in DB transfer regulation. Before this, the prevailing methodology relied on the Transfer Value Analysis System (TVAS), which attempted to calculate a “critical yield”, the investment return required in a DC arrangement to match the benefits being given up in DB. In practice, the critical yield often confused clients, over-emphasised investment performance, and downplayed the unique value of DB guarantees.

PS18/6 retired TVAS and introduced a new twin framework: the Appropriate Pension Transfer Analysis (APTA) and the Transfer Value Comparator (TVC).

The APTA required advisers to move beyond a single number and instead produce a holistic, client-specific analysis comparing staying in the scheme with transferring. The TVC, meanwhile, presented a visual bar chart showing the cost today of buying equivalent guaranteed income with an annuity, set against the CETV offered by the scheme.

The APTA should not be based on a purely hypothetical drawdown. To meet regulatory expectations, advisers need to model the analysis against a specific receiving scheme and underlying portfolio (including charges, investment strategy and glidepath). Where appropriate, consideration should also be given to an available workplace pension as the receiving vehicle.

PS18/6 also hardwired into the rulebook the presumption of unsuitability: advisers must start from the position that a transfer is not in the client’s best interests and only move away from that stance if robust evidence justifies it.

This presumption remains the key starting point for any DB transfer advice. It shifted the burden of proof: advisers must now build a case that a transfer is in the client’s best interests, rather than assuming it might be suitable and then working backwards. That subtle change has underpinned every compliance file since.

Guidance on “what good looks like”

By 2021, it was clear that many advisers were still struggling with the FCA’s expectations. Files remained inconsistent, and too often the presumption of unsuitability was treated as a box to be ticked rather than a principle to be applied.

The FCA responded with Finalised Guidance 21/3 (FG21/3). This document remains essential reading for anyone involved in DB transfers, not least paraplanners and PTSs. It walks through what the regulator regards as “good” practice: client objectives clearly recorded and assessed, APTA and TVC outputs integrated into the narrative, Attitude to Transfer Risk (ATTR) assessed separately from general risk tolerance, and suitability letters that balance pros and cons rather than presenting transfers as foregone conclusions.

Abridged advice

Running alongside these changes was the introduction of abridged advice in 2020. The FCA recognised that full advice processes were costly, and many clients could be ruled out early. Abridged advice allows advisers to provide a regulated, documented assessment that can conclude either “do not transfer” or “unclear”. It cannot conclude “transfer”.

If the result is “unclear”, the client must proceed to full advice, at which point the APTA, TVC, cashflow analysis, and full suitability report are required.

Abridged advice has been valuable in practice, particularly in cases where clients approach with little understanding but high enthusiasm. It provides a regulated stopping point, backed by documentation, that gives clients clarity without subjecting them to unnecessary costs. From a paraplanning perspective, abridged advice also reduces wasted work, allowing firms to filter unsuitable cases efficiently.

Consumer Duty

From July 2023 onwards, the FCA’s Consumer Duty began to shape how all advice, including DB transfers, is delivered and recorded. The Duty introduced a new principle: that firms must act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers. For DB transfers, this raises the bar considerably. Advisers must not only follow the process but also be able to demonstrate that the recommendation leads to a demonstrably better outcome compared to staying in the DB scheme.

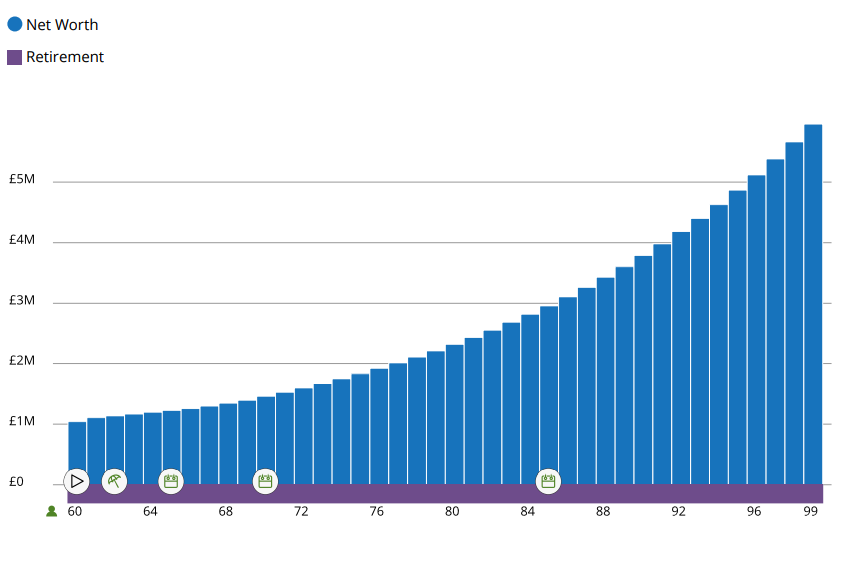

What this means in practice is that files must now explicitly evidence outcomes. A suitability report cannot simply state “we believe this is in your best interests”; it must compare what the client’s retirement looks like if they stay in the DB scheme with what it looks like if they transfer, under realistic assumptions, and then show how the recommended path produces outcomes aligned with the client’s objectives. This places even more importance on cashflow modelling and stress testing, because they are the most compelling way to illustrate outcomes.

We find it helpful to map outcomes to objectives as follows:

| Client objective | Metric | Stay in scheme | Transfer | Evidence source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility of income | Ability to vary withdrawals | Fixed scheme pension | Full control over drawdown | Cashflow model |

| Death benefits | % of fund payable | 50% spouse�s pension | 100% fund (IHT exposure from 2027) | Scheme rules, legislation |

| Certainty | Inflation-linked income | Guaranteed RPI-linked | Market-dependent | APTA/TVC |

The compliance lens

Put simply, today’s regulatory environment is the toughest it has ever been. Advisers are expected to:

- Apply the presumption of unsuitability.

- Document objectives clearly and interrogate them properly.

- Prepare APTA and TVC analyses aligned with actual portfolios.

- Integrate cashflow modelling that shows both base and stressed outcomes.

- Evidence Consumer Duty outcomes explicitly.

- Triage unsuitable cases through abridged advice.

For paraplanners and PTSs, it presents both a challenge and an opportunity. A well-prepared file today is not simply about passing compliance checks; it is about creating a narrative that is transparent, evidence-driven, and defensible years later should the advice ever be scrutinised.

When Might a Transfer Be Appropriate?

The FCA’s starting point could not be clearer: all DB transfers must be treated as presumed unsuitable. This is not a technicality, but a principle baked into the regulatory architecture since PS18/6. Advisers are expected to adopt a sceptical stance from the outset. Every transfer case is therefore an uphill journey, where the adviser must build and document a compelling evidence base to justify the recommendation.

That being said, suitability is not theoretical; it is specific to the client. Transfers are sometimes appropriate, but only when client objectives, household circumstances, health, tax planning, and financial resilience all align. To put it plainly: there must be a strong, multi-faceted rationale that can withstand both compliance scrutiny and the test of time.

The drivers of suitability

The most common driver is flexibility of income. DB pensions provide a steady, inflation-linked income stream, but they are inflexible. Clients cannot front-load withdrawals, vary income significantly, or take ad hoc lump sums beyond the pension commencement lump sum (PCLS). For some, this rigidity clashes with lifestyle goals. A 60-year-old might want to retire fully at 61, draw a high level of income until State Pension kicks in at 67, then reduce withdrawals thereafter. A DB scheme cannot deliver that shape. A DC arrangement can. But this flexibility comes at the cost of guarantees, and the question is whether the client can tolerate the risks that accompany it.

Another driver is household context. Suitability is not assessed in isolation; it must account for the client’s wider financial position, including their partner’s pensions and assets. Consider a household where one spouse has a secure DB pension covering core expenses. In such cases, the other spouse’s DB may be less critical for household security, opening the door to flexibility and estate planning opportunities. Conversely, when both partners are heavily reliant on a single DB, surrendering guarantees is far less defensible.

Health and life expectancy also play an important role. For clients in poor health, the value of a guaranteed, lifelong income is diminished. A CETV may allow them to access greater resources earlier in retirement or pass more wealth to their heirs. However, health must be evidenced, not assumed. It is not enough for a client to “feel” they won’t live long; the adviser must probe carefully, record medical history, and if possible, obtain supporting documentation.

Tax and estate planning is increasingly relevant in the post-LTA world. While the abolition of the LTA removed a major barrier to pension saving, the new Lump Sum Allowance and Lump Sum and Death Benefit Allowance add complexity. DB schemes typically provide taxable survivor pensions, which are subject to income tax and often less flexible. By contrast, DC pensions have until now offered more attractive estate planning potential, as pots could fall outside the estate for IHT purposes and be passed on flexibly within LSDBA limits.

However, this landscape is shifting. The government has confirmed that from 6 April 2027 most unused pension funds and lump-sum death benefits will fall within the scope of inheritance tax. Personal representatives will be responsible for reporting and paying the tax. Importantly, death-in-service benefits from registered schemes will remain outside scope. Draft legislation has been published following consultation, but advisers and clients should note that the detail is still subject to the passage of final legislation. Further HMRC guidance is expected before implementation.

This change significantly weakens the intergenerational planning case for transferring DB benefits into DC purely for IHT reasons. For wealthy clients, flexibility and control over death benefits may still be attractive, but from 2027 the tax efficiency advantage will be curtailed. Estate planning can therefore remain a factor in transfer discussions, but it must sit alongside stronger drivers such as household resilience, flexibility of income, or health considerations, rather than standing as justification on its own.

Finally, the client’s wider balance sheet matters enormously. A client with multiple DB pensions, significant ISA and GIA assets, and other secure income sources may justifiably use one DB transfer to create flexibility. By contrast, for clients with little other wealth, surrendering their sole DB security almost never passes the suitability test.

Case study: “Security outweighs flexibility”

Take the case of a 62-year-old client with a CETV of £400,000 and a promised DB pension of £25,000 per year, RPI-linked, with a 50% spouse pension. The client has £100,000 in ISAs and no other pensions. Their spouse has minimal provision.

The APTA shows that replicating the DB income with the CETV would require a much higher return than is realistic. The TVC confirms that the CETV is insufficient compared to the annuity cost of the guaranteed income. Cashflow modelling demonstrates that, while a drawdown strategy could meet income needs in the base case, the plan collapses under sequencing risk or extended longevity. The spouse’s dependency makes the guaranteed survivor pension particularly valuable. In this scenario, the presumption of unsuitability holds true, and the adviser is able to clearly evidence why the transfer is not in the client’s best interests.

Case study: “Flexibility supported by context”

Contrast this with a 58-year-old client holding a DB pension of £40,000 per year and a CETV of £1.2 million. Their spouse has their own secure DB pension of £30,000 per year. The household also holds £600,000 in ISA and DC assets. The client, unfortunately, has a medical condition that significantly reduces life expectancy.

Here, the household’s core spending is already covered by secure income, even if the client’s DB pension were transferred out. The CETV is generous, and when modelled through cashflow analysis, a transfer allows the client to enjoy higher spending earlier in retirement, while still maintaining long-term household security.

Estate planning opportunities have historically strengthened the case for transfers, since DC pots could fall outside the estate and be cascaded tax-efficiently. However, the confirmed 2027 reforms mean that most unused pension funds and lump sum death benefits will fall within the scope of inheritance tax. In this case, the client’s reduced life expectancy still makes a transfer potentially attractive. It allows resources to be accessed sooner, rather than left stranded in an inflexible DB income stream, but the adviser must carefully evidence that the benefits are primarily about lifetime flexibility and household security, with estate planning treated as a secondary consideration that will become less potent after 2027.

In this instance, suitability is not automatic, but a reasoned case can still be made. The adviser can document how flexibility, health, and household income resilience combine to justify the recommendation, while clearly acknowledging that estate planning advantages are diminishing and should not be relied upon in isolation.

Drawing the line

Suitability is not about whether a client “wants” to transfer. It is about whether their objectives and circumstances can support the risks they would take on by transferring. Death benefits alone are almost never enough. Flexibility must be backed by resilience. Health must be evidenced. Household context must provide a safety net. And the adviser must be able to show, in black and white, that the client will be better off relative to the counterfactual of staying in the DB scheme.

That is the standard today. Anything less risks failing both the FCA’s expectations and Consumer Duty requirements.

The DB advice process

The advice process for DB transfers is highly structured, not by chance but by regulatory design. Every step has been codified to reduce the risk of unsuitable advice, and every step must be present in the file. Advisers who take shortcuts inevitably leave weaknesses that compliance, PI insurers, and in the worst cases, the Financial Ombudsman will expose. In 2025/26, the expectations are clearer than ever: a DB transfer file should read like a complete story, with each stage logically building on the last.

Step 1: Fact-finding and objectives

Everything begins with the fact-find. This is not a tick-box exercise, but the foundation upon which all analysis rests. The adviser must capture a full picture of the client’s financial situation, health, and objectives. It is here that objectives must be probed in depth. A client who says they “want more flexibility” should be asked what that means in practice. Do they intend to retire earlier? Draw more income in the first ten years? Fund a child’s house deposit? Support grandchildren? Travel extensively? Objectives that are vague will crumble under compliance scrutiny; objectives that are specific, measurable, and evidenced can be tested against outcomes.

Health and vulnerability assessments are also critical at this stage. A reduced life expectancy may alter the value of guarantees, but this must be documented with supporting evidence. Vulnerabilities, whether financial, emotional, or cognitive, must be flagged and considered throughout. In the Consumer Duty era, firms are expected to demonstrate how vulnerabilities have been identified and addressed.

Step 2: Gathering scheme data

With scope agreed and objectives captured, the next job is to assemble a complete, verifiable picture of the existing scheme. Advisers shouldn’t simply rely on the information contained within the statement of entitlement but request a full information pack from administrator to so they can map out and rebuild the pension exactly as promised, tranche by tranche, so the APTA, TVC and cashflows reflect reality rather than assumptions. This should include:

- Scheme structure (Final Salary/CARE/hybrid), service history, tranche breakdown (incl. pre-97/post-97/post-2005 and any GMP elements), and normal retirement age for each tranche.

- Deferment revaluation basis, in-payment escalation (CPI/RPI/LPI caps/collars or fixed rates) per tranche.

- GMP detail (if applicable), pre-88/post-88 split, revaluation method in deferment (fixed or s148), who provides increases in payment, equalisation status and any adjustments.

- Commutation options and structure of income – current commutation factors, maximum tax-free cash, any step-up/step-down or bridging options, and whether factors differ by tranche or date.

- Early/late retirement factors, minimum ages allowed.

- Cash commutation factors.

- Spouse’s pension percentage, unmarried partner eligibility and evidence required, children’s pensions (amounts, ages, cessation rules).

- Protected pension age, protected tax-free cash, section 9(2B) rights, AVCs and how they can be taken, ill-health/serious ill-health provisions, buy-in/buy-out status and any trustee policy that affects transfers.

- CETV guarantee date, whether partial transfers are allowed, calculation hints where disclosed (discount rate references, mortality, inflation).

- Latest funding statement/summary, any member communications relevant to transfers.

Compile this into a scheme-data appendix (source and date each item), reconcile it to the member’s latest statement, and resolve discrepancies with the administrator in writing before you model a penny.

Step 3: APTA (Appropriate Pension Transfer Analysis)

The APTA is the analytical backbone of DB advice. It is designed to move advisers away from the old TVAS “critical yield” and towards a holistic comparison between staying in the DB scheme and transferring to a DC arrangement.

A good APTA will:

- Reflect the client’s intended post-transfer investment strategy. Using generic assumptions is not enough; the analysis must be aligned with the portfolio the client would realistically hold.

- Incorporate household income needs, tax implications, death benefits, and risk capacity.

- Model outcomes over the client’s expected lifetime, not just a short projection.

- Integrate objectives into the analysis. If the client wishes to retire early, for example, the APTA should model whether this is achievable with the CETV under realistic assumptions.

The APTA is not a spreadsheet exercise but a narrative tool. It should tell the story of why staying in the scheme or transferring produces better or worse outcomes for the client.

Step 4: TVC (Transfer Value Comparator)

Alongside the APTA sits the Transfer Value Comparator (TVC). This is a mandatory visual representation showing the CETV against the estimated cost of buying equivalent guaranteed income with an annuity, based on FCA-prescribed assumptions. The TVC is simple in appearance, but its purpose is powerful: to anchor the client’s understanding of what they are giving up.

The FCA has consistently criticised advisers for including TVCs in appendices without commentary. A good file does not simply drop the chart in; it explains what it means in plain English. If the CETV is lower than the comparator, the file should note that the client is receiving less than the actuarial “value” of their benefits. If the CETV is higher, the adviser should explain why that does not automatically make the transfer suitable, since investment risk remains with the client.

Step 5: Cashflow modelling

Cashflow modelling is where the analysis becomes real for the client and auditable for the file. Strictly speaking, the FCA does not mandate cashflow modelling for DB advice; what is mandatory in full advice is the APTA and the TVC. In practice, though, cashflows are the evidence engine that lets you compare “stay” versus “transfer”, demonstrate Consumer Duty outcomes, and show how the plan copes when things go wrong. Without them, it is very hard to evidence suitability. A robust model will include:

- A base plan or “current position” scenario, incorporating the client’s DB pension, any other savings, investments, and pensions that they hold, any other household savings, investments, or pensions, and realistic expenditure both now and in the future. It should include the State Pension where applicable and use realistic long-term return and inflation assumptions.

- A “what if” scenario, incorporating the CETV as a flexible DC pension with a corresponding withdrawal strategy. Again, this scenario should take a household view and use realistic long-term return and inflation assumptions.

- Stress tests, such as poor sequencing in the first five years, lower-than-expected returns or even a market crash, higher inflation, or longevity to (or sometimes beyond) age 100.

- Tax overlays, showing how the Lump Sum Allowance and LSDBA interact with withdrawals and death benefits. This is particularly important where tax or death benefits are being cited as a reason for transferring.

The goal is to demonstrate resilience, or lack thereof. A file that only shows a base case will fail compliance checks; a file that includes stress tests shows that the adviser has considered the full spectrum of outcomes.

Step 6: Suitability report

This is where the file comes together. A single, durable-medium document that reads as a clear story from fact-find and objectives through APTA/TVC and cashflows (if used) to a balanced recommendation. A strong report will:

- State objectives clearly and show how each was tested (amounts, timing, purpose), including any vulnerability considerations and reasonable adjustments made.

- Document Attitude to Transfer Risk (ATTR) separately from generic risk tolerance, and evidence capacity for loss in terms that relate to the model.

- Summarise scheme data succinctly: escalation/indexation by tranche, commutation and early/late factors, survivor terms, GMP underpins/equalisation status.

- Include TVC and explain, in plain English, what the bars mean for the client. Tie the APTA to the intended post-transfer portfolio (not a generic growth rate) and link both directly to the recommendation.

- Walk the reader through cashflows (if included): side-by-side stay vs transfer, base case and stresses (sequencing, lower returns, higher inflation, longevity, survivor view).

- Cover tax explicitly. LSA/LSDBA usage, MPAA triggers, wrapper sequencing, explanation of the April 2027 change bringing most unused pension funds/lump-sum death benefits into IHT scope, so estate outcomes are understood pre/post-2027.

- Present a balanced recommendation, including rationale and how it helps to meet the clients stated and tested objectives, potential disadvantages resultant from giving up a guaranteed and inflation-linked pension, and state all risks clearly.

- Set out costs and charges (platform/fund/adviser) and show their impact within the analysis.

- Include withdrawal guardrails, rebalancing, cash buffer policy, review cadence, and triggers for de-risking.

- Disclose assumptions, limitations and uncertainties (data gaps reconciled, reliance on administrator information), and confirm client understanding/acknowledgements.

The language matters as much as the numbers: keep it plain English, front-load the trade-offs and risks, and make the logic chain obvious. A good report lets a fair-minded reviewer see, at a glance, why the recommendation is in the client’s best interests.

How outsourced paraplanning adds value

The process of advising on DB transfers is demanding. It requires detailed technical analysis, careful documentation, and a sensitivity to both regulatory expectations and client understanding. For many advisory firms, particularly smaller practices or those without in-house specialists, this workload can be overwhelming. This is where support from a suitably qualified and experience outsourced paraplanner comes into its own.

Why outsourced paraplanning matters in DB transfers

Unlike many areas of financial planning, DB transfers are unforgiving. A small omission in data gathering, a weakly explained TVC, or a failure to stress-test cashflows can expose both the client and the adviser to serious harm. Compliance teams and PI insurers are acutely aware of this, which is why they scrutinise DB transfer files more heavily than almost any other type of advice.

Outsourced paraplanners bring two advantages here: technical expertise and dedicated focus. Advisers spend their days in client meetings, relationship management, and business development. Paraplanners specialise in building the technical and documentary backbone that makes advice robust. By separating the two, each professional plays to their strengths.

The qualifications that matter

Not all paraplanners are equipped to handle DB transfers. A PTS qualification is mandatory for advising on transfers, and paraplanners working in this space must understand the same regulatory expectations as advisers. Having a PTS involved in the preparation of APTAs, TVCs, and suitability reports provides reassurance to compliance officers and PI insurers alike.

In my case, I have been a Qualified PTS since 2019, with exam passes in RO4, JO5, AF7, and AF8 – essentially the full suite of pension qualifications offered by the Chartered Insurance Institute. This breadth of study matters because DB transfers are not just about pensions law. They touch on taxation, estate planning, trust work, and advanced retirement modelling. A paraplanner without this depth risks missing important nuances.

The support I offer for DB transfers includes:

- A forensic review of the scheme pack you provide, reconstructing the benefit entitlement under the existing scheme so the “stay” path reflects reality. I confirm overall structure, how benefits revalue and increase, the options that shape income, dependant terms and the GMP position; reconcile figures to member statements/CETV; sanity-check factors and escalation; and flag anomalies with precise follow-ups. The output is a concise scheme-data appendix, and issues log that feed straight into Selectapension APTA/TVC (and cashflows, if used).

- Preparing the APTA and TVC. Building the analytical comparison between staying and transferring, aligned with the client’s intended portfolio, and producing the mandatory TVC with accompanying narrative.

- Building detailed and comprehensive cashflow models, stress-testing for poor returns, high inflation, sequencing risk, and longevity, and showing outcomes under both “stay” and “transfer” scenarios.

- Preparing the Suitability Report, using either your template or one that I have prepared for you, weaving together objectives, analysis, and outcomes into a coherent narrative that explains the recommendation in client-friendly language while satisfying regulatory requirements.

For advisers, this means less time spent on the technical tasks, and more time with clients. For compliance teams, it means receiving files that are structured, consistent, and easier to review.

Efficiency and cost-effectiveness

DB cases are time intensive. Even a relatively straightforward case can take six hours of paraplanning work, while complex cases can take longer. For a firm trying to manage a pipeline of multiple clients, this workload quickly becomes unmanageable. Outsourcing provides flexibility.

My own pricing model is straightforward: an hourly rate of £85, with a typical full case, including APTA, TVC, and a full suitability report, requiring around six hours. This transparency allows advisers to plan costs accurately. Because there are no retainers, firms can scale up or down as their pipeline demands. If DB enquiries are quiet, costs fall; if interest surges, capacity can be increased.

Integration with adviser processes

Some advisers worry that outsourcing means losing control. In practice, outsourced paraplanning works best as an extension of the adviser’s own process. Files are prepared under the adviser’s branding, using their chosen software (whether Voyant, Truth, or CashCalc for modelling), and reflecting their house assumptions. The adviser remains responsible for client interaction and final sign-off; the paraplanner provides the technical infrastructure.

This partnership allows advisers to focus on the human side of advice: listening, coaching, empathising, while paraplanners ensure that the technical underpinnings are watertight. Clients experience a seamless service; compliance officers see complete, well-documented files.

Value beyond compliance

Although compliance is the primary driver, the value of outsourced paraplanning goes beyond box-ticking. A well-prepared report is also a communication tool. It helps clients understand the trade-offs they face, the risks they are accepting or avoiding, and the rationale for the recommendation. In many cases, clients find that the clarity of a paraplanner-drafted report is what finally helps them make peace with the decision – whether that decision is to transfer or to stay in their DB scheme.

DB transfers are not routine. They are exceptional cases where the stakes are high and the risks significant. For advisers, the challenge is balancing rigorous technical analysis with client-facing responsibilities. Outsourced paraplanning solves that problem. Advisers who partner with experienced, qualified paraplanners are not just outsourcing workload; they are buying peace of mind.

Conclusion

Defined Benefit pensions remain one of the most valuable assets most clients will ever hold. They provide guarantees that are increasingly rare in modern finance: inflation-linked income for life, protection for surviving spouses, and freedom from the investment and longevity risks that dominate the rest of retirement planning. These guarantees are expensive to replicate in the open market and, for most people, irreplaceable.

The adviser’s task is not to find reasons to transfer, but to test client objectives against the value of what would be given up, and to document those findings with clarity. In most cases, the right advice is to remain in the scheme, however tempting flexibility or lump sums might appear.

And yet, transfers are not extinct. The current environment has sparked renewed interest. CETVs, while far below their 2019 peaks, have edged up from the lows of 2023–24. Schemes are more strongly funded than they have been in years, creating confidence and prompting more enquiries. Tax reform has reshaped the conversation: the abolition of the Lifetime Allowance and the introduction of the Lump Sum Allowance and Lump Sum and Death Benefit Allowance have made estate planning through pensions more prominent. Clients are asking questions again.

The conclusion, then, is twofold. First, DB transfers are likely to remain rare and should be treated as such. They are the exception, not the norm, and every case must be tested against the presumption of unsuitability. Second, where transfers are suitable, they must be evidenced to the highest standards. There is no room for shortcuts. Only by maintaining this discipline can advisers protect their clients, satisfy regulators, and safeguard their own businesses.

For those advisers who continue to operate in this challenging but important space, the message is clear: stay rigorous, stay documented, and do not go it alone. The value of qualified, experienced paraplanning support has never been greater. By combining client-facing empathy with technical expertise, advisers and paraplanners together can deliver advice that is compliant, compelling, and truly in the client’s best interests.

Disclaimer: We provide consultancy services to support advisers in the DB pension transfer advice process. However, the responsibility for ensuring the suitability of advice remains solely with the adviser. We are not authorised or regulated by the FCA and do not provide or take responsibility for regulated advice, including DB pension transfer recommendations. This article is for information only and does not constitute personal advice.